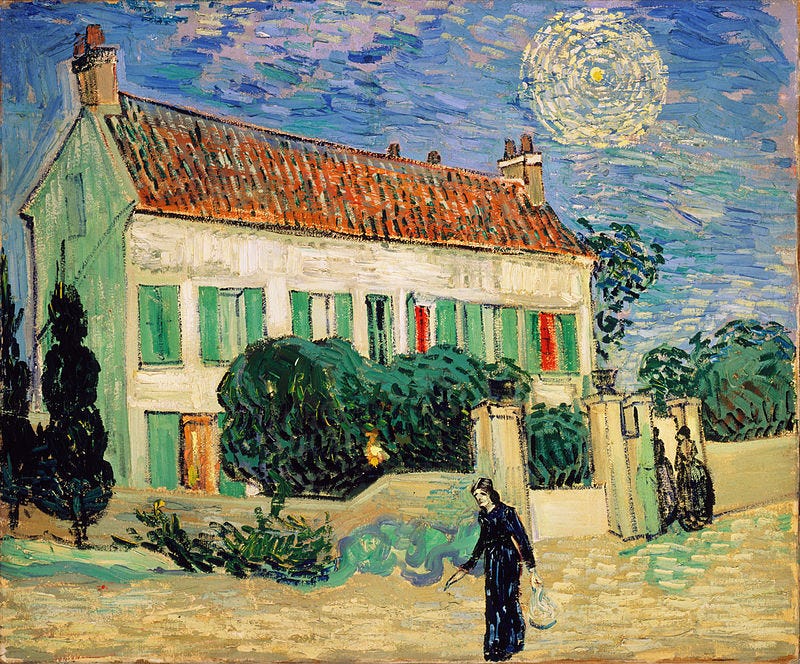

Believed to be painted only six weeks before Vincent’s tragic death - The White House uses a slightly more plain colour scheme than some of the other works in his final weeks . . . and yet, still, carries a markedly intense, almost alarming, quality (even by Van Gogh’s standards!)

The trees here seem literally to be quivering in fear, rather than swirling in passion as they do in many of Vincent’s other masterpieces

And the lone woman in the foreground may well be one of Vincent’s saddest characters . . . carrying herself with the air of someone utterly broken and scarred by this life. (Though it is unclear whether she is walking away from the house she has just left . . . or is simply hurrying past a home that once belonged to her, yet now holds a tragic memory)

But to really see the underlying psychological tension in this painting - which is undoubtedly a reflection of Vincent’s own mind state at this time - I think it will give us a lot of value by comparing this to the great man’s other most iconic “home” portrait.

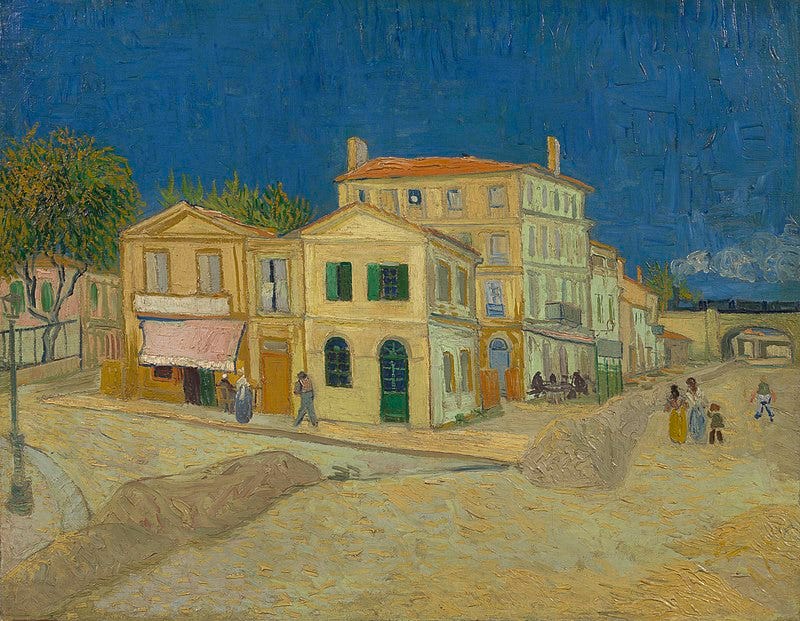

The unmistakeable “Yellow House” - which he painted two years earlier in 1888, soon after first arriving in the town of Arles, with his dreams of founding an artist colony.

Here, we of course see how Vincent’s unique “irregular perspective” gives his buildings a really unique character..

But in general, the tone of this street scene is peaceful, warm, and almost romantic; with our young family walking together to the right - and a cute steam train passing over the bridge in the background.

We can clearly see just how enchanted Vincent was with his new “little yellow house” . . . or, rather, how in love he was with the idea of what this place would become for him.

Yet when we now return to The White House - located roughly 400 miles north of Arles, in the small town of Auvers-sur-Oise, where Vincent lived out his final days - we see just how this former sense of hope had started to feel much harder to hold on to.

This house- whoever it may have belonged to - is painted in brilliant light considering this is supposed to be a Night scene. Yet clearly, it no longer has that smooth warmth and glowing walls of Vincent’s Arlesienne idyll.

Instead, this house is almost like a kind of pale faced monster; standing very much alone (as Vincent himself did, far too many times), and with those red light windows, symbolizing bloodshot eyes.

Then, we look to our main figure in the foreground here - so mournfully walking away from the house, without even a look back. (Perhaps signifying the many people Vincent felt had deserted or given up on him over the years)

And of course, there is the sky too - where we notice that single blazing star, so very isolated up there in the heavens,

Perhaps through religious eyes, some might draw parallels to this being intended almost a kind of “star of Bethlehem”.

But, in all honesty, I do not think Vincent is really intending any biblical undertones here.

Rather, I think we should interpret this star quite literally - i.e this is exactly what Vincent was seeing on this particular night. And, in seeing things in that literal manner, the emotional resonance of such a small detail becomes even more impactful. Because just for a moment, put yourself in Vincent’s position here.

Imagine looking up at the night sky, and seeing a single spot of starlight pulsating like this. . . with such a vast aura of light, that it seems almost to be reaching down for you.

In the right frame of mind, perhaps such a sight would be inspiring. But, more than likely, if you were already feeling a little vulnerable . . . the whole thing would be nothing short of terrifying!

You might start to worry that you had lost your mind . . . or that your grip on reality may never return to how it used to be, when all the world seemed so full of divine beauty.

And no doubt, this was very close to how Vincent would have felt at this point in his life too - where even the smallest emotional triggers were feeling so overwhelming to his fragile senses.

Frankly, it is incredible that he was still able to work at all. Yet, for Vincent, painting was no longer optional.

Art had so often been his means of expressing his deepest emotions and for pursuing his highest ideals. But, more than anything, it was his way of clinging on to beauty - because, just as Fyodor Dostoevsky had once written too, Vincent fully believed that “Beauty will save the world”.

And so, essentially, that is at the heart of his White House painting too; that even in the midst of a growing crises, with loneliness overwhelming him, and all the world seeming to be grow darker or more troubling by the day . . . still, Vincent continued to set out with his easel and his paintbrushes, in an attempt to find light in this life.

_

What a truly remarkable man.

All contributions are immensely appreciated, and play a vital role in the future of this newsletter.

Alternatively, if you would rather not take a subscription but still want to support with a single / one off donation at a price of your choosing, please use the button below.

Thank you George. I have researched the skies in 1888 in Europe to see if there were any celestial events, because I find it so interesting that Vincent painted the sky like that. • The sky over France in 1888 featured notably bright objects (like Venus), and there were unusual meteor reports, which may have inspired Van Gogh. Could be Venus. ? Thank you again for an interesting comparison between two 😊.

Another gem - thank you! Not unique to Van Goch, but especially relevant here, is how we can project into or perceive this kind of universal art as what makes us human. It’s how we experience a masterpiece as much as the masterpiece itself (which makes it a masterpiece of course)