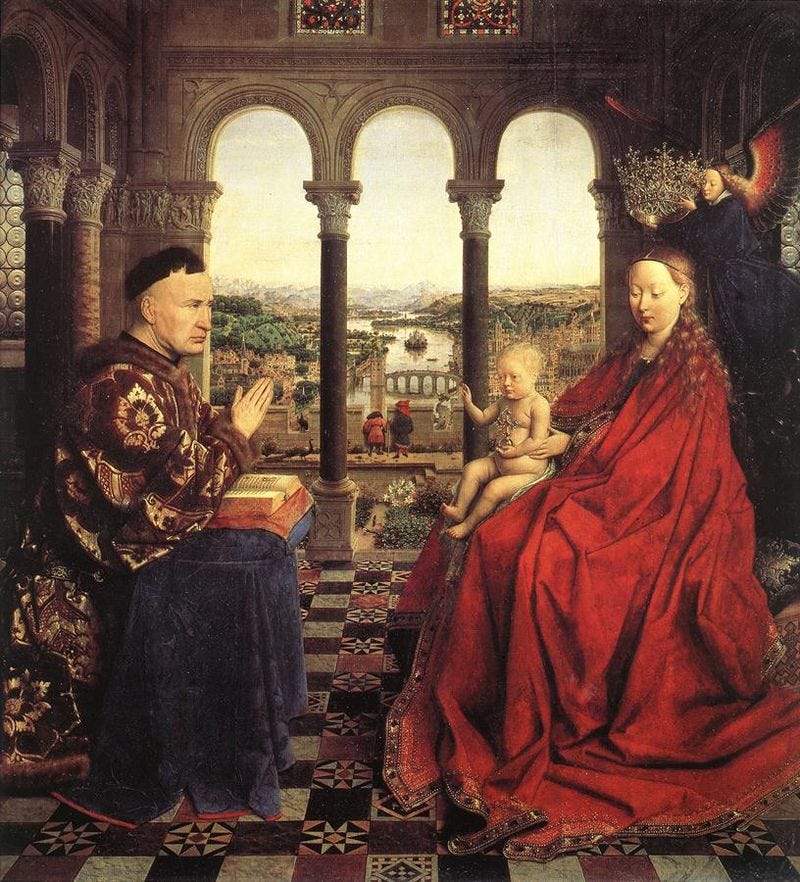

Jan van Eyck is a seminal figure in the history of Western art.

As a pioneer of the Northern Renaissance, he is often regarded as “The man who invented oil painting” . And while that might not be fully true - there is no doubt he achieved a realism in his work that had never been seen before.

In fact, it is a quality which has rarely been seen since too; even 600 years from when he was in his prime.

Sadly, almost nothing is known about Jan’s early life - thus, we do not fully know where he learnt to paint with such astonishing detail. (It is highly likely that he would have served an apprenticeship or trained in a workshop much like all artists of the time - though equally, self education must have played a significant part here too, simply because no other Netherlandish artist of the time could paint like this!)

But when it comes to his professional life, the details are a little better. And we know that Jan’s work was always in high in demand for pretty much his entire career; both for his secular/commissioned portraits, and later while he was serving as court painter to the Dukes of Burgundy and Bavaria respectively.

So with that in mind, it is quite a shame that nowadays we only know of around 20 works which can be confidently attributed to Van Eyck’s hand- especially as he lived at least in to his mid fifties or early sixties, which was a fairly respectable age in those times.

Sadly, this suggests that a vast quantity of his oeuvre has been lost to history. Although, it could also mean that van Eyck was simply a slow worker - more interested in achieving perfection, than in a prolific output.

Whatever the case may be - it it quite clear that Jan was incredibly ahead of his time with his painterly talent. And this leads me on to one of the other facts I love most about Van Eyck . . . that he was actually one of the only 15th-century Netherlandish painters with the audacity to sign his canvases.

His standard signature - “ALS ICH KAN” - was essentially like his own personal bit of branding. But, also, it is interesting to note how these words can be interpreted in a few different ways.

_

Firstly - the phrase can be seen a relatively simple pun on his name (I.e when spoken aloud, the words “Ich Kan” sound fairly similar to “Eyck” or “Eyck-ian”)

Secondly, in their translated form - Als Ich Kan roughly means "As Best I Can" - which, I’m sure you will agree, is a wonderfully humble way of signing off a work. (And reminds me also of the only time the great Michelangelo ever signed one of his own works too . . . when, in carving his name into his Pieta sculpture, he used the phrase “Michelangelo was making this”)

But, lastly- there is a third way to interpret Jan’s signature here too. And, personally, I must admit this is my favourite of all!

You see, the phrase ALS ICH KAN could also be translated much more boldly - meaning “As I Can”. Or, more specifically “AS ONLY I CAN!”

And in many ways, that would make more sense here - because remember, we are dealing with a man who was already breaking contemporary standards by having the audacity to even had a signature on his works.

So, for that reason, I think it is safe to assume that van Eyck was not exactly short on self confidence. And yet, there is a kind of playfulness to this phrase too.

_

He is not denigrating anyone else’s work, or literally declaring he is greater than all others.

Rather, he is just prodding us with a gentle reminder that he really is in a league of his own here.

He is top of the list.

Second to none.

“As only I can!”.

_

And while humbleness is a virtue . . . perhaps a healthy degree of arrogance is perfectly justified too, when one actually has the talent to back it up.

Bonus work

No article on Jan van Eyck would be complete without a reminder of his most iconic work The Arnolfini Portrait.

If you are a paid subscriber, do feel free to check out my longer deep dive into this highly mysterious work in my article published here last year.

I remember your wonderful discussion of the Arnolfini portrait. I just realized that Van Eyck seemed to be fortelling the woman as being the bearer of her husband’s children. A mysterious promise of fruitfulness.

I saw the headline and was thinking, "As only I [George] Can." Fair enough!